For almost a decade now I have been working, in my writing and in my museum work, to make the story of American history more honest and accurate. Beyond making a few people uncomfortable, I haven't made much impact. Yet.

I will persist.

I am no longer working regularly in museums, but I still visit them frequently. Last weekend I visited the Peabody Essex Museum, in Salem, Massachusetts. I am fond of this museum, and tour it at least once a year. It is a beautiful space with art from all over the world that is expertly curated and always impressive. My daughter and I had gone down specifically for the Georgia O"Keeffe exhibit (I'll post about that later), but this time I noticed there wasn't much going on at the museum in celebration of Black History Month. Nothing at all that I could see. (In fairness, the PEM does have an extensive collection of African Art but it is not currently on view.)

And it got me to thinking, how easy it would be to remedy that, especially in the American Art wing where I found this:

I will persist.

I am no longer working regularly in museums, but I still visit them frequently. Last weekend I visited the Peabody Essex Museum, in Salem, Massachusetts. I am fond of this museum, and tour it at least once a year. It is a beautiful space with art from all over the world that is expertly curated and always impressive. My daughter and I had gone down specifically for the Georgia O"Keeffe exhibit (I'll post about that later), but this time I noticed there wasn't much going on at the museum in celebration of Black History Month. Nothing at all that I could see. (In fairness, the PEM does have an extensive collection of African Art but it is not currently on view.)

And it got me to thinking, how easy it would be to remedy that, especially in the American Art wing where I found this:

While it was noted (in the small marker pictured above) what was most noteworthy about the people featured in the large portraits, I wondered how relatively easy it would be for the museum to make other connections to black history in the American Art wing with similar markers, or maybe something more eye-catching. I am sure there are countless, fascinating connections that could and should be made to African Americans both well known and unknown as well as to events related to black history in the art pieces on exhibit in that wing, and all of them could be noted near the art as was done here with the Phillis Wheatley connection.

We went on a tour of three historical houses that the PEM maintains, and the tours were also completely bereft of black history. I asked the tour guide what she knew of one of the house's history of slaves and servants, and she quickly replied there was none, telling me the date that slavery was abolished in Massachusetts which was a good half century after the house was built. I'm not insisting that the house owners were slave owners but I certainly question it. Either way it is simply not possible that the three houses we toured have no black history to share. Salem played a major role in the slave trade, from shipping fish to the West Indies to feed the enslaved there, to sending and financing slave ships back and forth across the seas.

It is important, critically important, to tell these stories. As I have told people I've worked with at history museums in New Hampshire and Maine, if we are not telling the whole story than we are not telling the truth. Historians can't cherry-pick the history they tell. The public is entitled to the truth. The public wants the truth. The public needs the truth.

As a teacher I think of bringing children of color into these public spaces and it makes me angry. We can do better. Much better. Not just in February, but February is certainly a time to be examining what visitors see and hear.

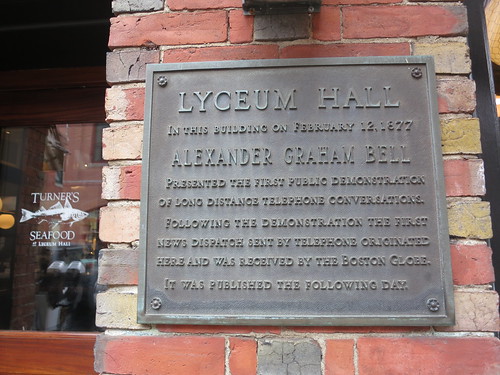

And just so I'm not singling out the PEM for criticism, I am disappointed to add that we had an early dinner at a restaurant nearby called Turner's Seafood that I chose because it was housed in a historic building. I was hoping to learn some of its history when we visited, but found none inside nor on the restaurant's website. Later research shows that it too, has a significant history to share and is listed as site #3 of African American Heritage Sites in Salem as chosen by the National Park Service who notes:

3. Salem Lyceum

43 Church Street

The Salem Lyceum opened in 1831, and its rows of banked

seats quickly filled with residents of Salem eager to watch

demonstrations, lectures, and concerts. Nationally known

artists, politicians, philosophers, and scientists, including

Daniel Webster, Alexander Graham Bell, and Ralph Waldo

Emerson came to speak in the building. Many activists in

the abolitionist movement came to the Lyceum as well, such

as William Lloyd Garrison. In December 1865, Frederick

Douglass lectured in the hall on the assassination of

President Lincoln.

The Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society

The hall was also used for meetings and lectures by the

Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, whose members

included the noted African American abolitionists Charlotte

Forten and Sarah Parker Remond. Charles Lenox Remond

gave the Society’s anniversary address in 1844 and was

frequently asked to speak as part of the Society’s ongoing

lecture series.

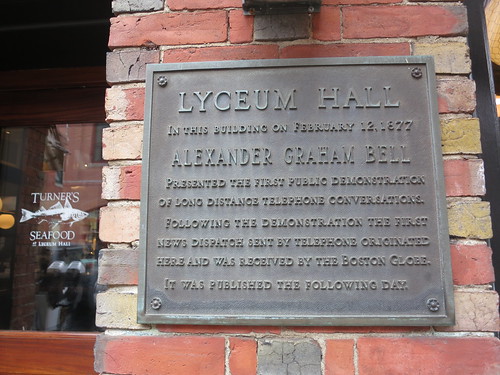

How I wish I had known that while we were in the building. Apparently we missed this plaque rushing to get in out of the cold.

It feels a tad ironic to me that the hall's original mission was to supplement those with incomplete educations and that the first lecture given there was entitled "The Advantages of Knowledge."